The AWS Outage: Why This Was Not Amazon’s Fault,…

The recent AWS outage is not Amazon’s fault. It’s the fault of companies that built for high availability (HA) instead of disaster recovery (DR). HA means multiple availability zones (AZs) within a single region; DR means multi-region resilience. Only one AWS region—US-East-1—was affected. Those who went down have only themselves to blame.

Summary of the Incident

On October 20, 2025, AWS experienced a major outage in its US-East-1 (Northern Virginia) region. The incident lasted roughly 9 to 15 hours, depending on the service, with some companies reporting degraded operations for longer. The issue was traced to a DNS resolution failure following a faulty API update to Amazon DynamoDB. This update broke endpoint resolution for DynamoDB and related authentication services, triggering timeouts across dependent infrastructure.

Within two hours, AWS engineers isolated the problem and initiated parallel recovery. By mid-morning U.S. time, most services were restored, and by the afternoon, AWS declared the issue fully mitigated. The company’s incident response and communication were swift, transparent, and professional.

Yet, thousands of companies and major apps—from Reddit to Snapchat, Coinbase, and OpenAI—went dark. Over 17 million outage reports were logged globally. Why? Because even though only one region was affected, many architectures were fatally dependent on it.

Why is US-East-1 so popular anyway?

The US-East-1 (Northern Virginia) region is AWS’s oldest, largest, and most interconnected region—essentially the backbone of Amazon’s global cloud infrastructure. It offers the widest range of services, lowest latency to major U.S. population centers, and earliest access to new AWS features before they’re rolled out elsewhere. Because it’s deeply integrated with global DNS, IAM, and S3 control-plane systems, many organizations default to US-East-1 for critical workloads and management operations. Its size and maturity also make it a cost-effective and high-performance choice, which is why so many companies—sometimes to their detriment—rely on it as their primary region.

Only One Region Was Affected — So Why Did Others Fail?

AWS clearly stated that the failure was confined to US-East-1. No other regions were directly affected. So why did global services crash?

Two main reasons:

- Cross-region dependencies — Many systems, even those running in Europe or Asia, still authenticate users or fetch metadata from US-East-1. Services like IAM, S3, and DynamoDB are often regionally anchored, and too many organizations hard-code dependencies there for convenience.

- Third-party providers entirely reliant on AWS (and often on US-East-1 specifically) — Some supposedly independent services—like Docker Hub and Atlassian Confluence Cloud—are heavily integrated with AWS infrastructure. Docker Hub’s image registry reportedly depends on AWS ECR (Elastic Container Registry) under the hood. When ECR endpoints in US-East-1 went dark, pulling containers from Docker Hub also failed globally. Similarly, enterprise tools like Confluence and Jira Cloud experienced cascading failures because their authentication and API layers are hosted in the affected region.

In short, this was not a global AWS failure—it was a global architectural failure among companies that put all their eggs in one regional basket.

The Big Misunderstanding: High Availability vs. Disaster Recovery

The tech industry loves to brag about being “highly available.” But high availability (HA) and disaster recovery (DR) are not the same.

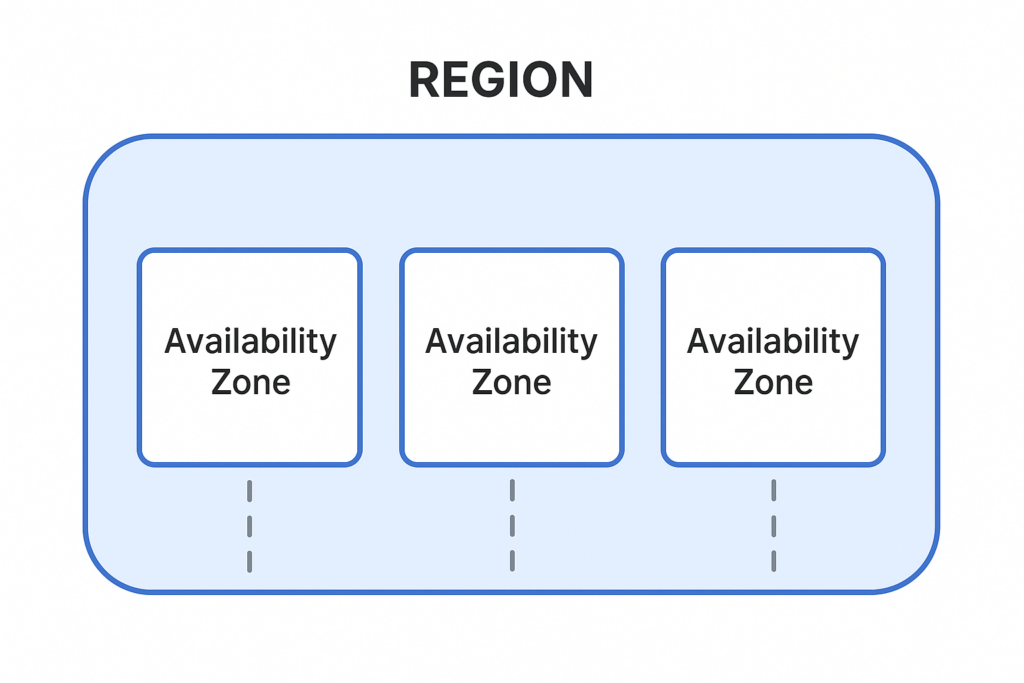

- High Availability (HA) = Resilience within a single AWS region, spread across multiple Availability Zones (AZs). It protects against hardware or datacenter failures, not regional outages.

- Disaster Recovery (DR) = Resilience across multiple AWS regions (multi-region). It protects against catastrophic regional failures—like this one.

Fig 1. One AWS region contains several Availability Zones. Even major companies have made the mistake of treating AZs as if they were regions. Outages almost never happen, anyway… Well, not really!

Too many teams stopped at HA, mistaking it for DR. They deployed across two or three AZs in US-East-1 and congratulated themselves on being “redundant.” But when the entire region went down, their so-called redundancy evaporated.

Why? Because true disaster recovery requires replication, orchestration, and routing across different geographic regions. It’s harder and more expensive—but it’s what AWS has been advising for years.

AWS’s Official Disaster Recovery Strategies (and Why Most Ignore Them)

AWS has been extremely clear about this in the Well-Architected Framework, under the Reliability Pillar. It defines four disaster recovery strategies, each with increasing resilience and cost:

- Backup and Restore – Periodic backups stored in a separate region. Cheapest, slowest to recover.

- Pilot Light – Core infrastructure (databases, minimal app services) always running in another region. Quick to scale up when needed.

- Warm Standby – A fully functional but smaller copy of your environment runs in another region. Can scale up quickly. Middle ground for cost and reliability.

- Multi-Site (Active/Active) – Fully redundant systems in multiple regions, simultaneously active. Most resilient, most expensive.

These are documented in the Reliability Pillar (REL13: “How do you plan for disaster recovery?”). AWS even provides calculators and example architectures. Companies ignoring these guidelines are not victims—they’re negligent.

Implementing DR is indeed costly and complex. It requires:

- Managing cross-region data replication (e.g., DynamoDB Global Tables, Aurora Global Databases)

- Multi-region load balancing and failover routing (Route 53, CloudFront)

- Testing failovers regularly

But AWS has made these tools available for years. Those who chose not to use them prioritized cost savings over reliability.

Conclusion: AWS Is Not at Fault — Companies Are

AWS did its job. One region failed—not the entire cloud. The company recovered the issue in under a day (though some customers were impaired for almost twice that time), communicated transparently, and had redundancy across its global network.

Companies that went dark didn’t suffer from an AWS outage—they suffered from their own architectural laziness. Anyone with a Warm Standby or Multi-Site setup stayed online. Everyone else chose to save a few dollars per month, and this week they paid the price.

Nine to fifteen hours of downtime in years of uptime is not AWS’s failure—it’s a lesson. If you gamble on cost over resilience, you can’t complain when the storm hits.

AWS has delivered world-class reliability. The only ones who failed are those who didn’t listen.